I hope you all had the opportunity during our fine extended spell of stunning weather to experience just how much fun it is to play golf at Machrihanish Dunes when the fairways are burnt out and golf balls run forever on the rock-hard surfaces.

Although these conditions create a few headaches and a bit of extra work for us greenkeepers, we would never wish it any other way. We remain upbeat about the weather even when our free evenings are taken away from us because we have to come down and water greens in order to keep them in good condition, for in truth there are few more glorious places to be on a sunny evening than out on the Kintyre coastline.

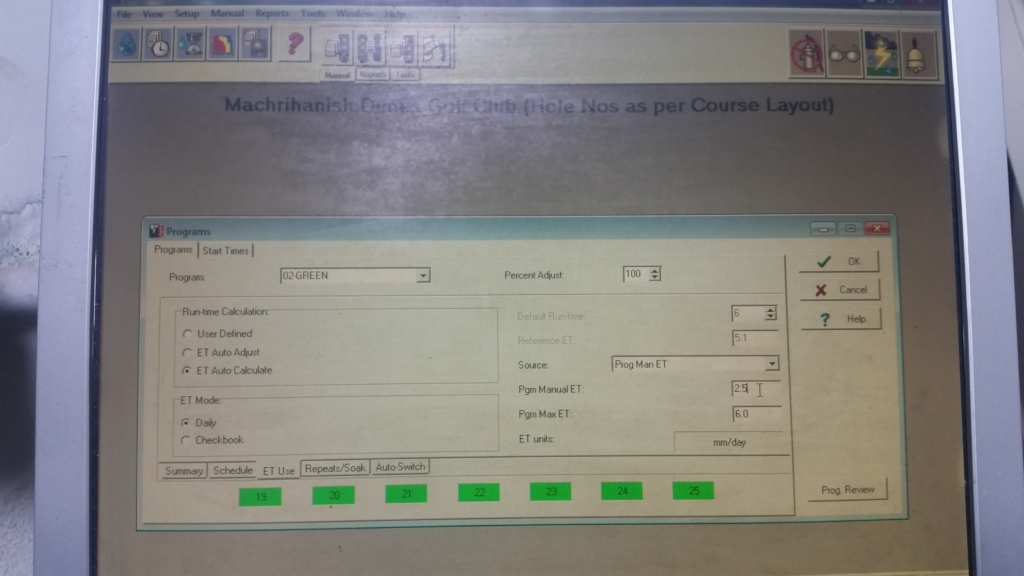

Managing our resources in the most efficient way possible can be both stressful and rewarding. For me, the stress comes from having to rely on things that are outwith my control to keep the course in the best condition possible. Our water is pumped from 16 well points situated near the golf house into two large holding tanks at our maintenance facility. From there another pump feeds a closed underground circuit of pipes that spur off at every green to provide a water feed for several automatic sprinklers and a coupling point where we can attach a hose. Programs can be set up on a computer in our office to provide solenoids at each sprinkler with a defined signal that supplies each green in turn with an exact, pre-determined amount of water.

This system is absolutely brilliant and saves countless hours of manpower while providing the greens with water at the very time they need it (the middle of the night when it has the best chance of penetrating into the soil without losing too much via evaporation). To be this good though, the system has to be quite complicated, and if any spoke in this elaborate wheel were to let us down at any time the results could easily be measured in terms of the drought damage caused to turf.

My biggest worry always comes from the potential for us to run out of water altogether. Any mechanical part of the system can be replaced in a relatively short period of time, but if that natural supply of water dries up on us then our mechanical resources are rendered completely useless. Luckily, we are in Scotland, so this has not happened to us yet, as dry spells of weather in even unusual years like this never tend to last for long and winters are usually wet enough to completely restock supplies. Relying on that knowledge doesn’t help me sleep any better at night during sunny periods, though, so I am always looking for ways to reduce the amount of water that I put on the golf course.

What we did during the recent dry spell in May and June was to concentrate our watering efforts on the greens and to water tees only when they were starting to suffer from wear. Dormant perennial grass wears out very quickly when subjected to wear from foot and machine traffic, but this eventuality can be avoided if you know from experience where the point of no return is. If you were to look at the course today you would see that the greens look entirely healthy, the white and yellow tees (the ones that suffer the most play) look pretty healthy, the red tees look a bit more burnt than that and the blue and black tees look like Ryvita biscuits. I know that those blue and black tees have a good percentage of perennial fescue and bentgrass plants growing in them—it is easy to keep them in good condition because they hardly get any play—so I know that I can afford to not water them at all because those plants have a mechanism whereby they can go into drought dormancy and then return to full green health when conditions allow. Likewise I know that the white and yellow tees contain more poa annua (due to the aforementioned wear issues and because these tees are covered in irregularities (i.e.divot marks) that provide ideal seedbeds for poa seeds to steel and establish) so I know that I cannot afford to take as many liberties with them without impacting negatively on their long-term health. The red ladies tees lie somewhere in between these two parameters.

Despite having one of the best automatic irrigation systems in the country at my disposal, I am a big fan of hand-watering. Looking back through the irrigation reports on my computer, it appears that we will use somewhere in the region of 45,000 litres of water to execute a 2.5mm automatic watering program. When 3 men go hand-watering with hoses to apply roughly the same amount of water, that figure is closer to 25,000 litres. That makes a huge difference because even when I know I can rely on my supply from the well points to provide me with a good return, I can only really expect to pump around 50,000 litres a day back into the tanks from there. With hoses and a human brain to operate them, we can apply water to exactly where we need it, focussing on burnt areas and high spots and avoiding wasting water by targeting areas that are not on the green itself. Obviously, a sprinkler has a triangular arc to complete as it goes through its cycle, and every time it reaches the ends of that arc the extremities of its spread are falling off the green rather than on it and that not only wastes water but also produces inconsistent golfing conditions. There are many evenings on the west of Scotland where it is also simply too windy to use an automatic irrigation system. They are very effective up to about 12mph, but once the forecast suggests that wind speeds will be elevated beyond that we know that results will be inconsistent and we make plans to hand-water the greens instead.

One thing we experiment with a lot at Machrihanish Dunes is wetting

agents. These substances have been used for decades to ensure that when water is applied to a dry area of turf it can penetrate into that area rather than running off completely or collecting in low areas. The technological advances in this field have been huge in the last few years, and we can now choose from a variety of products that can help us manage the percentages of water in our rootzone and also how quickly that water travels from the surface to the subsoil.

A Quick Guide to Wetting Agents

Type 1: Penetrants

Penetrants. These are designed to help water to penetrate the surface, but they contain no technology to stop water from moving quickly all the way down to the subsoil. While a penetrating wetting agent may be very effective at keeping the surface dry and free from morning dew and pressure from disease, sandy rootzones treated with straight penetrants can dry out frighteningly quickly and may require a huge input of water in order to keep grass plants healthy.

Type 2: Matrix Flow

These are designed to hold water in the rootzone. Don’t ask me how they work…I could give you a basic explanation but it is far easier just to accept that they can do what is claimed and attribute it to voodoo! These products are obviously very popular with greenkeepers, as not only do they store water exactly where we need it to be stored but they reduce evaporation during hot spells by keeping rootzones cooler and therefore protecting roots from drought stress. The only downside to matrix flow wetting agents is that they keep rootzones more artificially saturated than we would actually like. Although we won’t argue with that when our backs are against the wall during a prolonged spell of hot, dry weather, we know that using a matrix flow wetting agent all the time will only play into the hands of that laziest and most inefficient of grass plants, poa annua. Saturation figures vary from product to product, but I don’t think I would be far away from the truth if I were to suggest that saturation point on a sandy soil when using a typical matrix flow wetting agent might be around 30-35%, whereas a healthy, untreated similar soil might never contain more than around 25%.

Type 3:

A third type of wetting agent has become available in recent years, and this one is designed to physically attract water to individual soil particles. This is brilliant when you think about it, because it holds a percentage of water in the rootzone while still allowing plenty of room for air, and seems at first thought to be the ideal answer to our water storage issues. It has been suggested that field capacity using these wetting agents is around 22-25%, therefore mimicking the moisture levels that would be found in an untreated sandy soil sample but actually containing far more available water which is stored exactly where it is most advantageous to the plant.

We have experimented with all three types of wetting agents at Machrihanish Dunes, and we use a variety of them for different reasons. Obviously, we resort to using a matrix flow wetting agent during the mid-summer months, but we wish we didn’t have to as it goes against everything else we are trying to achieve in our program. We have tried to use the third type of wetting agent mentioned in the box above during dry spells, but because our rootzone is so light and well aerated we have had issues with soil temperatures becoming rapidly elevated on days where the air temperature rises to over 20 degrees Celsius and this has exacerbated problems that we have had with fairy rings and dry patch. This year, we have been messing about on the tees by mixing two products together in order to see whether we can stretch the area affected by the matrix, reduce the percentage of water held in the rootzone at field capacity by that matrix, or even hold it lower down in the profile to encourage plants to root deeper and store water at a level in the rootzone where it is cooler and where evaporation is less of an issue. Results from these kinds of experiments are hard to quantify though—successes must be based on knowledge of the product and what we see happening in front of us. If we know products are designed to work in a certain way and we mix them because we perceive that a benefit can be gained on our particular site and for our particular maintenance program from doing so based on our knowledge of the science behind it and we do not encounter any negative consequences from conducting the experiment, then we can probably conclude that our experiment has been successful. It would be extremely brave to take a mixture like this from the tees onto the greens, where the grass is cut shorter and stresses are so much higher, but we wouldn’t shy away from doing this if we thought we were onto something (especially if we had the backing of a knowledgeable expert from the company supplying the materials and had discussed this with him at length).

Hydrophobia – the biggest fear of all

One of the main reasons why greenkeepers started to use wetting agents in the first instance was because they found that their intensively managed turf became hydrophobic when it dried out in summer and that it required huge volumes of artificial watering to keep it alive and to re-wet the whole soil profile. Most of the time, hydrophobic symptoms are caused by bacterial life in the soil, who munch through organic material deposited in the rootzone from decaying plants and then secrete a waxy material as a by-product that becomes hard and impervious to water when it dries out. Because this waxy material has been deposited in the upper rootzone, areas affected by this process will not be effectively soaked by irrigation water, as that water will be blocked by the waxy layer. Areas close-by that have not been affected by this bacterial activity may require only a small amount of water to completely soak the whole soil profile, while the area that has become hydrophobic may only be penetrated to a depth of a few millimetres, and can, therefore, dry out again extremely quickly when the sun comes back out the next day and evaporates everything that has been applied. There are several reasons why dry patch is such a huge problem on golf greens, the first of which is that levels of organic matter in the upper portion of the rootzone tend to be quite high as it is intensively managed. That portion of the rootzone tends to be rich in cellulose, and water levels near the surface are usually kept at a level that are favourable to the bacteria’s health. Finally, some of the daily maintenance practices that we undertake in order to produce firm, fast putting greens inevitably increase compaction levels and contribute to surface sealing.

Once a green has shown signs of hydrophobia during a dry spell, we have to be careful that we do not allow our turf to suffer from catastrophic drought stress. We know that water is not penetrating as it should, so we have to add more than we would like and we have to add it more often. Obviously, the poa annua that populates healthy, unaffected areas of the green loves this, as it is being watered far more regularly than the perennial grasses that it competes for space with really need it to be, and it flourishes in these conditions. The longer the dry spell goes on, the longer we need to keep applying too much water and the longer the spiral of decline continues. This kind of outbreak can be avoided or at the very least reduced if we implement a properly planned maintenance regime. If we keep our rootzones properly aerated, plan feeding programs to give our surfaces only what they actually need in order to survive, topdress regularly to dilute thatch layers, keep air circulating in the upper rootzone, and do anything we can to promote the growth of perennial grasses over the thatch-producing menace that is poa annua, then we have a chance of reducing or even completely eradicating outbreaks of dry patch and fairy rings, and then we will find ourselves in a situation where we can drastically reduce the amount of water that we need to pour onto our greens. This will reduce costs, reduce wear and tear on our irrigation equipment, help us still further to promote the growth of deeper rooting, perennial plants and will undoubtedly reduce the stress levels of the greenkeeper. One day I might actually be able to enjoy a spell of sunny weather rather than lying awake worrying about things and secretly praying for rain!!

What was that about restoring factory settings?

Okay, back to the beginning. When we have had a spell of dry weather that has lasted as long as the one we “endured” recently, our surfaces inevitably get a bit tired. The rootzones under the greens at Machrihanish Dunes are getting easier to manage, but they do still suffer from poor rooting and a bit of dry patch when they get stretched to the limit. Now that summer conditions have eventually reverted to the west coast average, we have finally had the opportunity to get an application of matrix flow wetting agent, some topdressing and some granular fertiliser out onto the greens and an application of our secret mixture wetting agent, a whole load of grass seed and sand and some fertiliser onto the tees. It is possible to apply these products and then water them in with our irrigation system, but we never have the amount of water available at any single moment to do this effectively so if we want these applications to work as they are designed then we need a suitable amount of rainfall. 10mm in a day just about covers it. Carefully planned applications of the correct products, washed in by 10mm of good old natural rain, restores factory settings. The sun can come back out now if it wants. We are good to go again!

What’s up next at Mach Dunes?

Our 36 hole stroke-play Club Championship is being held next weekend (28th – 29th June), and there are still times available if you wish to enter. After that, it is everybody’s favourite, the Black Sheep Cup, on Sunday, August 26th. For more information on either of these events, please phone Lorna or Peter at the Golf House on 01586810058. Apart from that, it is business as usual, except for a staff change here in the Greenkeeping department. Craig Barr is leaving us to take over as Head Greenkeeper at Machrihanish Golf Club and we wish Craig all the best in his new endeavour. He has been a fantastic servant to Machrihanish Dunes and the members at Machrihanish Golf Club are understandably delighted that they have recruited a greenkeeper of his calibre to help take their course forward. We have recruited Malcolm Mitchell to join us here at the Dunes. Malcolm has worked at Machrihanish Golf Club for the last two years as first assistant and we are looking forward to him starting work with us on August 6th.