Or is it? Sure, the days seem to get shorter once the clocks change, but I find that this time of year on the West coast of Scotland is rarely as bad as I expect it to be. We have certainly been enjoying our fair share of good weather lately. I always relate how I expect our grass to fare by comparing their health to how I feel myself. So if I am enjoying the late autumn sunshine, then I guess that the greens will be lapping it up too. This is why they have been performing so well. It has been easy to keep them in a state of almost suspended animation as we have managed to keep fertiliser inputs low, which has resulted in low-growth yields and only minimal attacks from disease pathogens. The result of the low yield and relatively good health has improved playability of the course since it becomes much easier to produce a fast, true surface if we are hardly removing any clippings when we cut the greens.

I am always aware of how quickly things can change at this time of year. If I react in a cautious manner when you tell me how good the greens have been good following an exceptional spell of weather, it is because I know from experience that there is always the potential for bad times to be hiding just around the corner. That is just the way it goes for greenkeepers. I suppose it will be the same for anybody who is charged with looking after any living entity. If you take your eye off the ball for a minute, you can spend weeks chasing your tail trying to get that ball back again!

Paralysis by Analysis

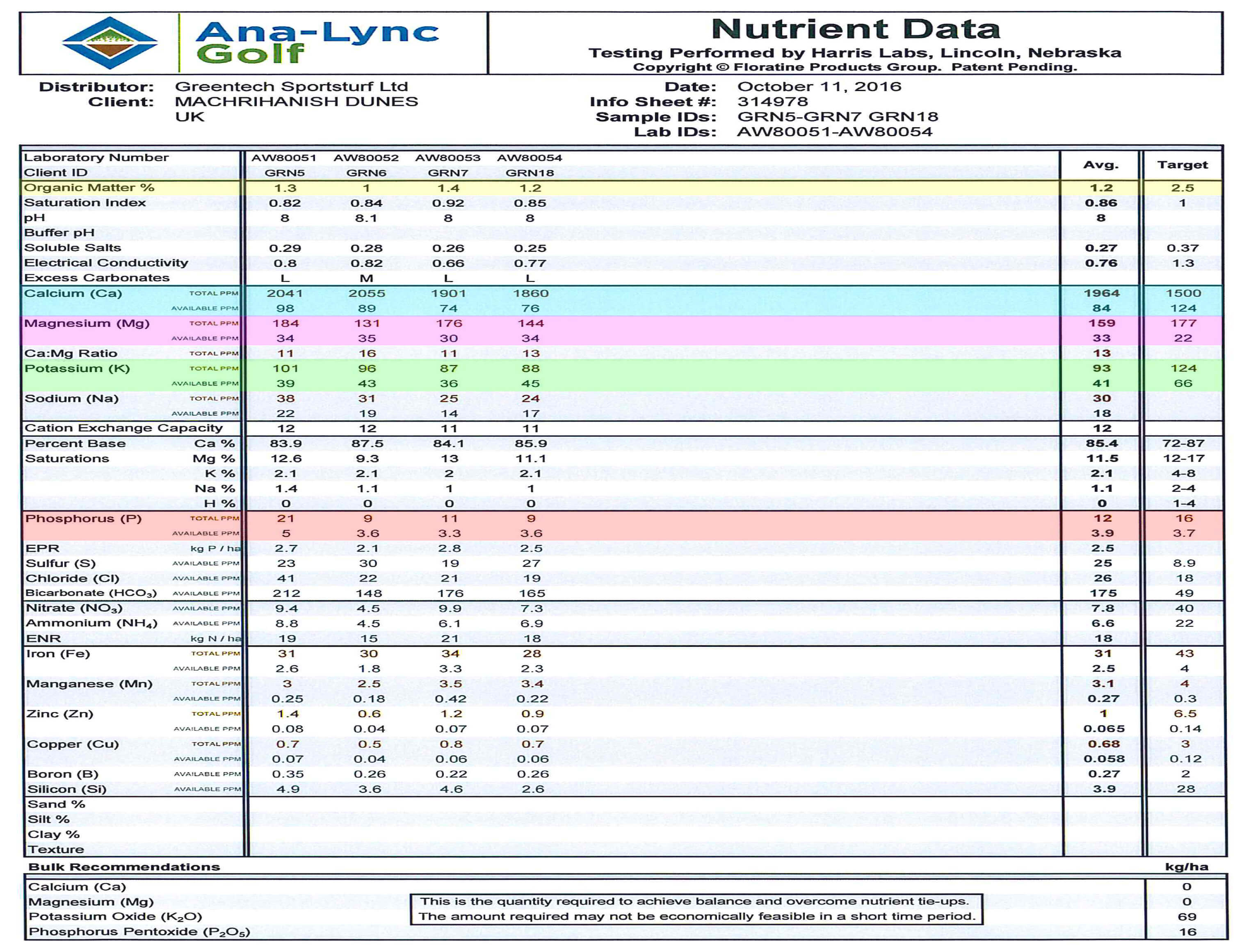

One of the tools we use to try and forecast problems is Soil Nutrient Analysis. We have recently sampled 4 of our greens at Machrihanish Dunes and had the results sent to us. Our greens were last analysed way back in 2011, it was interesting to compare the results from then and now as we try to guage how we are progressing in our quest to bring these young greens to full maturity. In the chart below, there are several indices that are of massive importance to us as we attempt to improve the physical make-up of these rootzones.

-

Organic Matter

This is a hot topic in Greenkeeping circles, as most established courses either have too much organic matter in the upper profile of their rootzones, or they think that they do! Excess organic matter, which builds up through leaf decay and the deposition of grass clippings, is the main cause of soft, thatchy surfaces. This results in slow, bumpy greens and outbreaks of turf disease. Preferential species of grass, such as fescue and bent, will be out-competed by poa annua in a rootzone that is too rich in organic matter. This aggravates the negative cycle, as poa annua is a plant that produces a lot of organic matter. The usual percentage range of organic matter in garden soil is considered to be between 2 and 10. I would expect any greenkeeper who has levels above 4 percent to be actively looking to reduce. This can be done by hollow-coring, applying light sandy topdressings and over-seeding with a preferential species of grass and then tailoring their maintenance regime in order to favour those species in preference to the dreaded poa annua. Their goal will be to reduce the level of organic matter in the rootzones to what is considered to be the holy grail of results: 2.5%.

You can clearly see from the Machrihanish Dunes results that our issues are the complete opposite of this: our organic matter levels range from 1% to 1.4%. I frequently write about how easy it is for us to manipulate these rootzones to provide surfaces that are good to putt on; a simple addition of one or two rolls a week or an extra cut can have a massively positive influence because the upper rootzones are so sandy and firm, and largely devoid of organic matter. There is a problem with this though: the preferential species of fescue and bent that we are trying to favour need to have a symbiotic relationship with the soil to survive. They cannot do that unless there is sufficient soil bacteria to form this bond. In order to survive, the soil bacteria need a supply of organic matter to work with. If they do not have this food source, they will starve to death and these grasses will not be able to form this natural bond that gives them a competitive advantage over poa annua during times of stress. In a perfect world, we should be able to use this natural bond that perennial grasses have with their surrounding environment to reduce inputs from fertiliser and water, starving out poa annua which cannot survive under these “links-like” conditions. However, if the rootzone is too inert to support the continued existence of these bacteria and micro-organisms, then the infrastructure of their world will collapse. Which will then require the fescue and bent to be fed and watered in the same way as annual grasses – and there is only going to be one winner in that scenario.

So how do we tailor our program in such a way that we enrichen these rootzones in the right way? Well, for starters, we have to think for ourselves rather than blindly following what everybody else is doing. Our set of “problems” are the complete opposite of what most other people are dealing with. The first thing I decided to do a long time ago was to avoid removing the precious organic matter that we do have. Although I do verticut occasionally during the mid-summer months to remove lateral growth and fine-tune the grass sward, I am careful not to go too deep – therefore avoiding the chance of removing organic material. I aerate a lot, but always with solid tines. I have never hollow-cored these greens, and cannot foresee myself doing that anytime soon. Aerating with solid tines ensures that there is sufficient air available in the upper rootzone. This will allow the low numbers of beneficial bacteria, which can survive healthily at current levels, to break down clippings and dead leaves into humus that provides the basis for a good source of food for themselves, for earthworms, and for uptake by grass roots. It does not remove any of the precious material that we have built up. Because we want to encourage the growth of perennial grasses, we deliberately keep fertility low. However, when we do feed the greens we use a balanced fertiliser with high levels of humus and micronutrients. The old adage that you should treat links greens with nothing but nitrogen only applies to greens that already have ample supplies of everything else, and that is not the case here. The current scenario does give us the opportunity to perfectly tailor our inputs and therefore build these rootzones up exactly the way we want them though, which is an idyllic position to be in!

The last weapon in our arsenal is topdressing. Many people use straight sand as their preferred topdressing medium, as that offers them the best dilution of their overly-rich rootzone. I can see the point in doing that in conjunction with hollow-coring, as it firms up greens instantly. I have always shied away from using straight sand as a regular topdressing (i.e. when used to build up a level of good material on the surface). This is because I believe that everybody needs to have some organic matter in the upper profile in order to preserve bacterial life. If we apply the recommended (i.e. massive!) amount of topdressing to golf greens per annum, then there is the potential for the top surface layer of the rootzone to become too inert and for the health of bacterial populations in that layer (the layer where we need them to live in order to work with our plant roots) to become compromised. The topdressing material we have been using for the last two years contains 80% sand and 20% soil. This material has been tested to show that it has an ideal organic matter level of 2.5%. If we keep building up the surface with this and keep following the rest of this program, we will take our organic matter levels in the right direction. This will result in an increased population of beneficial soil bacteria, which will then make it easier for us to grow the grasses we want to grow, which will, in turn, make our greens easier and cheaper to look after.

2) Nutrient Levels

There are so many figures contained within these results that you could get hung up on this subject forever, but there are a few useful factoids that have a major impact on how our greens perform. Calcium levels are high (as you would expect in a sand predominantly made up of shell), but not much of that is available to the plant. A high level of calcium is not in itself a major issue, but a knock-on effect of locking up other nutrients (especially phosphorus), making them unavailable to the plant. Our phosphorus levels (and available phosphorus levels) actually look alright, but this is definitely worth keeping an eye on. We have reduced the levels of locked-up calcium in our rootzones and have made it available to the plant by regularly using a spray product which is designed to do just that. Results in 2011 showed these greens as being massively deficient in magnesium. These latest results suggest we have made good progress in bulking up the rootzone with this nutrient. The ratio between calcium and magnesium is much more in line with optimum levels than it used to be! We were massively deficient in potassium 5 years ago, and we still are today, which tells me that we are either using all of what we are applying or we are losing it too easily due to leaching. Either way, we need to be extremely careful, because potassium is not only vital to plant health, it also competes with sodium in the pecking order of nutrients that plant roots uptake. Common sense tells us that our shoreside rootzones are going to be unusually high in salt (anybody who has played Mach Dunes in a westerly wind will attest to that!). The actual presence of salt is not an issue until there is the potential for the plant to take it up. If the grass roots cannot find an available source of potassium when they need it, then they will uptake sodium instead, with predictably catastrophic consequences. It is interesting to note that all the greens tested have similar levels of both soil attached and available potassium, but that the 5th green (the one we always struggle with in late winter) has a higher concentration of both chloride and bicarbonate salts than do the other three. So this winter I am going to experiment with an application of a slow-release granular potassium fertiliser. I will apply this just before I would expect the main gale season to start in early December. This should supply enough potassium nutrient to the greens to keep them topped up until March, and will hopefully avoid them up-taking any sodium from the soil. Let`s just see whether this has a positive impact on the health of these greens (and that 5th green in particular) going into spring, in comparison to last year.

This is all highly speculative and a lot of this unproven theorising is, of course, still just exactly that, despite me having the hard facts and figures right here in front of me. It does show the absolute need to have these rootzone analyses completed on a regular basis though. It also shows the need to apply the results to what we see on the ground and then to have the common sense and the flexibility to adjust our programs to suit our particular needs. I love a bit of science, so I do!

WINTER LEAGUE AND THE MEMBERS NIGHT

I mentioned our Winter League in last month`s update, and explained that entry was free, scores could be entered every Sunday between now and the last Sunday in March. The best 4-round final total will win the league and the mystery prize. The league is now well underway, so if you have not yet started amassing your 4-round total then you had best make arrangements to come down and play catch-up! There are plenty of Sundays still to come, but I am sure the weather will disrupt the schedule at some point.

That`s all for this month. I hope you enjoyed the science, and I hope you enjoy your golf as we head towards the last month of 2016!